The Front Castle

First week at Hone Tuwhare's Crib at Kākā point, with pictures x

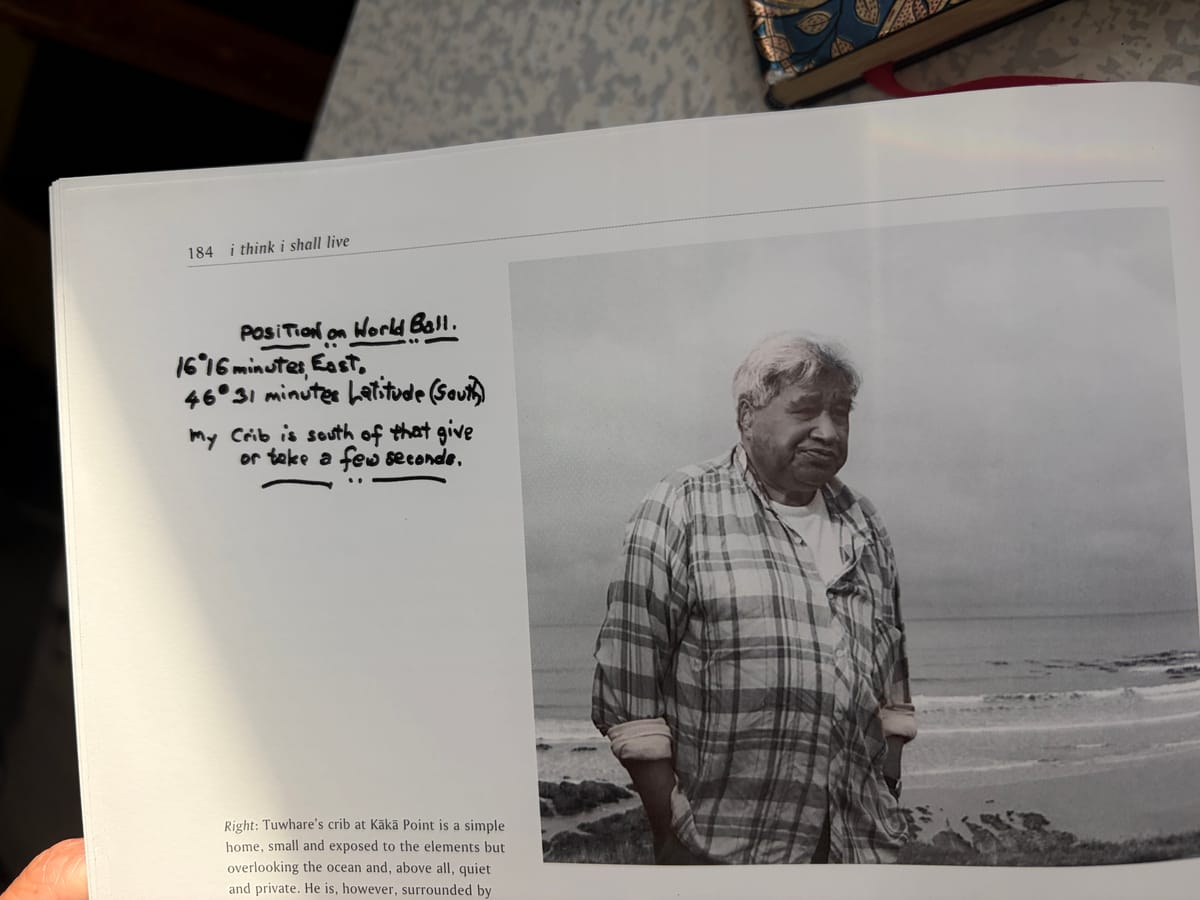

I'm here! At Kākā point. The Front Castle. Pāpā Hone's Crib. Latitude 46. Close enough to the ocean it feels like the crib itself is floating (and Hone did once describe himself as a boat, though there's plenty of innuendo going on there, as always with him).

In his biography, Janet Hunt describes the white caps beyond the window as a 'flicking mane'. I don't think I can describe it without reaching for cliche, or 'pre-loved language' as John Huria would say. But there isn't anything clichéd about waking up to a horizon so bright it zaps your eyes in their sockets. Waves hit the shore like applause*

Gissa smile, sun!

Pics from some spectacular days. *The ocean is compared to applause in Hone's poem, Kākā point.

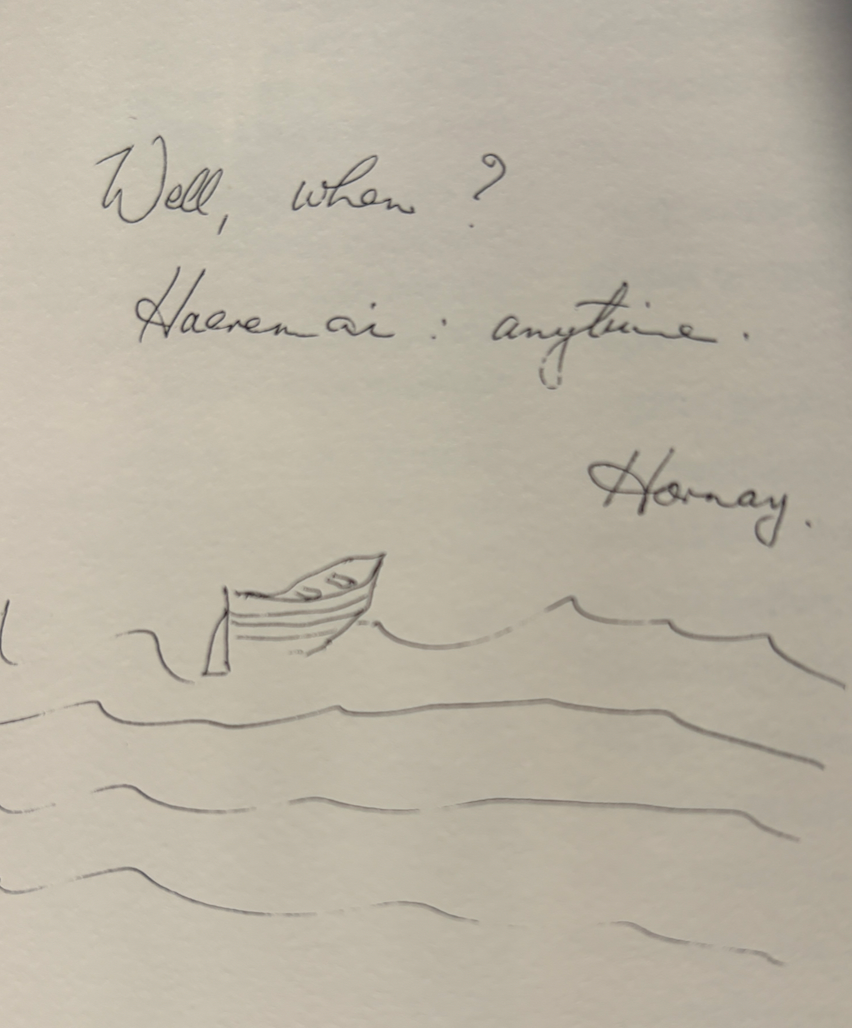

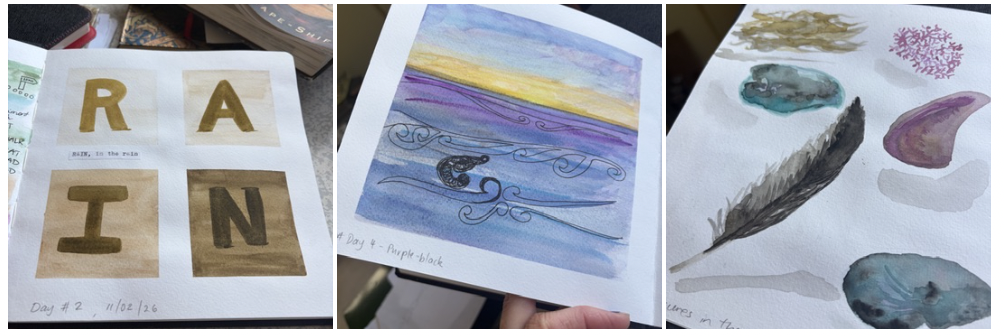

I read Hone's biography from cover to cover on the first day then picked up Shape Shifters. After that I started on Patricia' Grace's Small Holes in the Silence - a short story pairing to aching perfection (seriously, my heart did ache a lil bit). Actually, all I have done since I got here is read. Read and sleep and eat and walk and chill, and also paint and sketch very-quite-amateurishly.

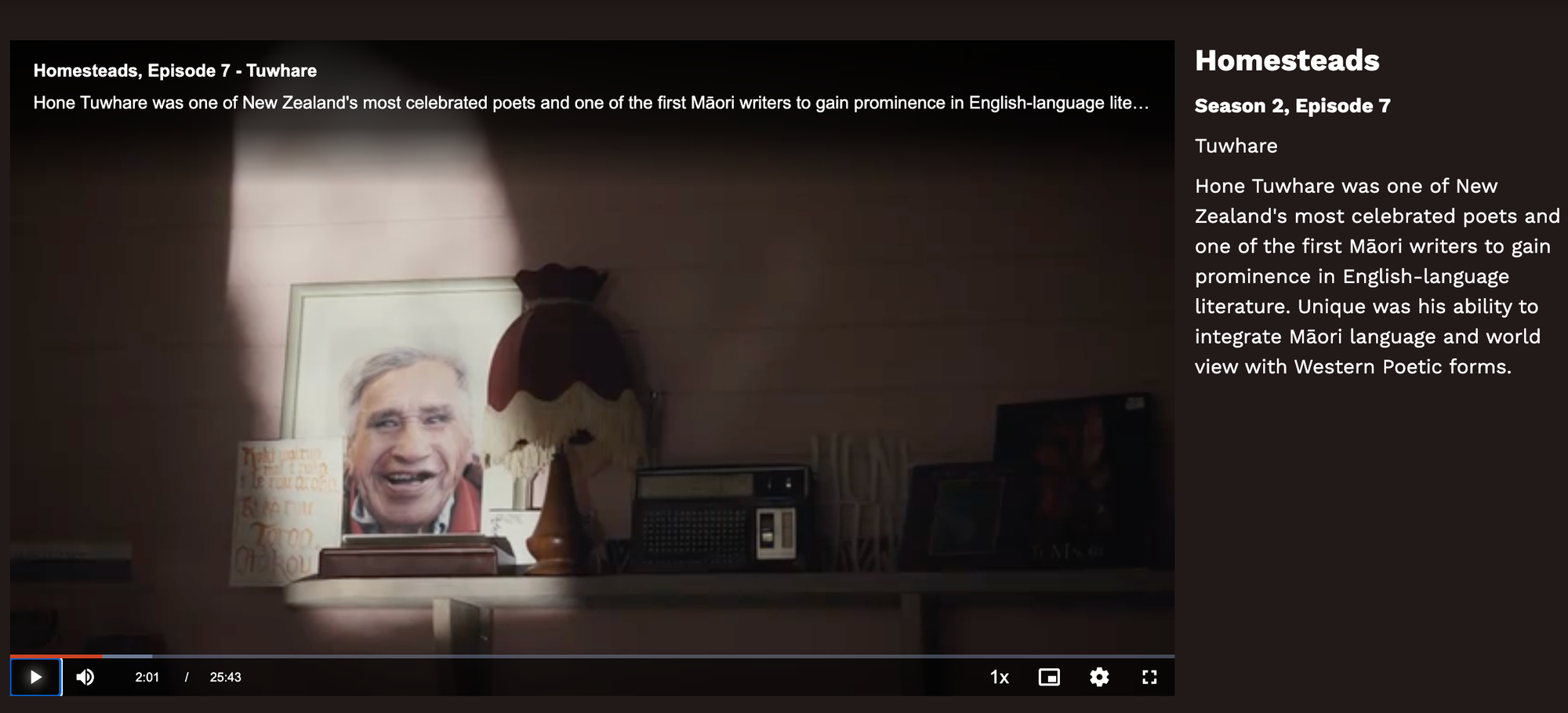

My favourite part of the day has been sitting up late listening to interviews and documentaries. I began with Gaylene Preston's 1996 film where Hone refers to the room I'm sitting in now as "the front castle". Then I re-watched the 2021 documentary Wind, Song and Rain featuring his granddaughter's poetry braided together with his in the most lovely intergenerational karanga. I've also been playing Don McGlashan's harmonica-infused interpretation of "Friend" on repeat (can't be found on Spotify, but must listen here at 7.35s).

But the one I most recommend - to really get a close-up view of, and feel for this place - is the Homesteads doco (in fact if you wanted to you could just watch this and skip my whole post lol):

My own writing has been a bit stop-start. The jitters, Haimana said. Fair enough. When I flung back the ranch slider door and saw Hone's delighted face beaming down at me I just froze. Thinking: is this real? It took me ages to step across the threshold. Eyes going in all directions, to all the treasures glinting on every shelf and wall, sketches and scratchings on kelp and windowpane, each one brought and laid by previous manuhiri and not one identified by name - but you can take a punt, every ringatoi has their own signature and style and lovely uniqueness. Same as Hone. Singular. Imitating no-one.

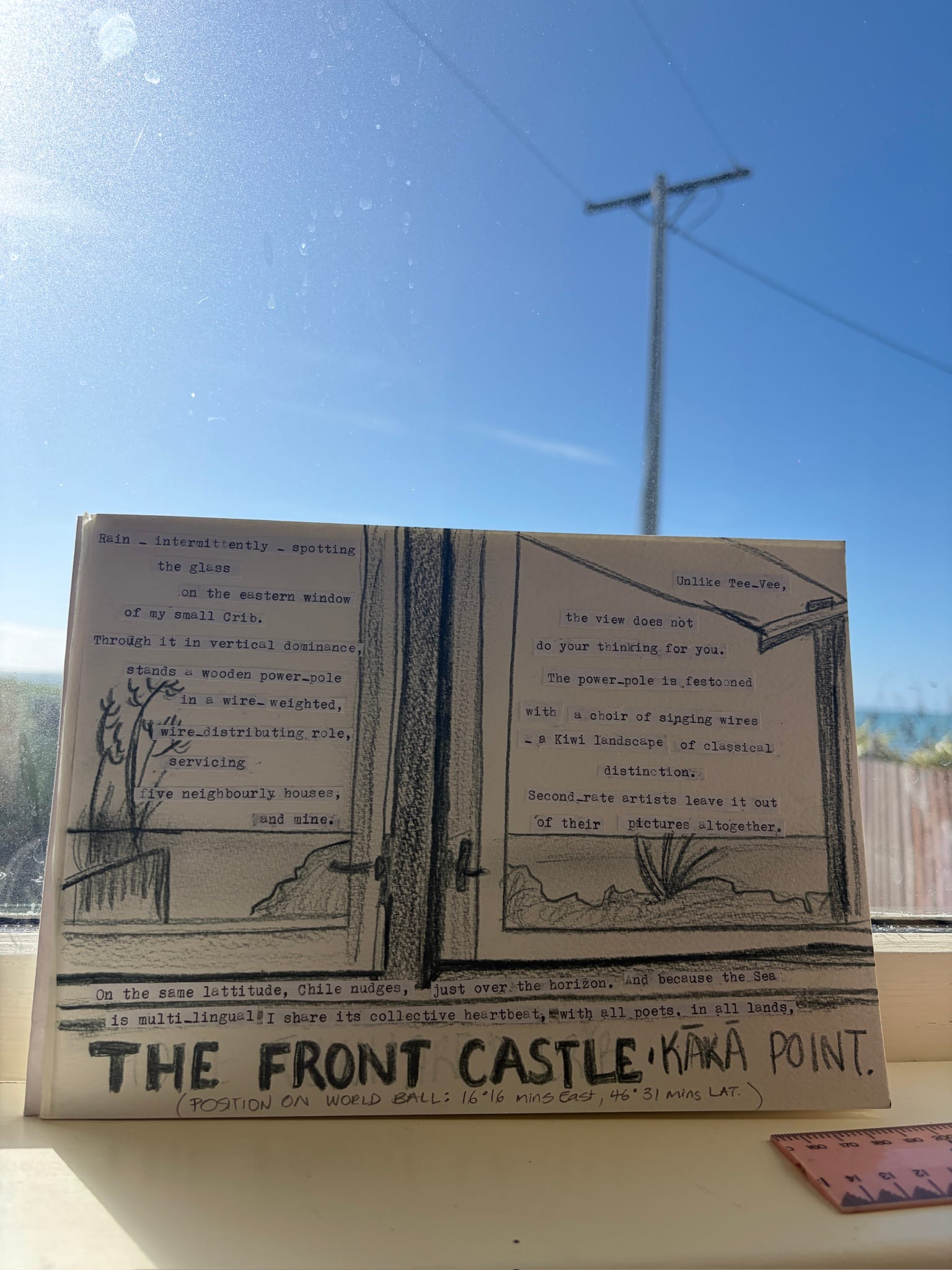

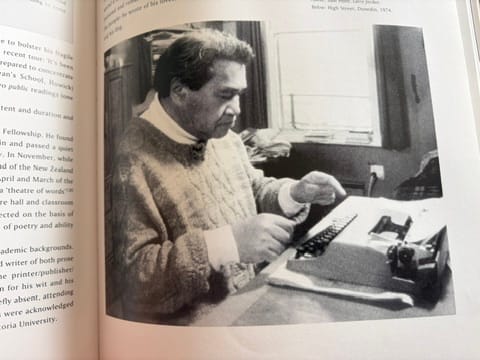

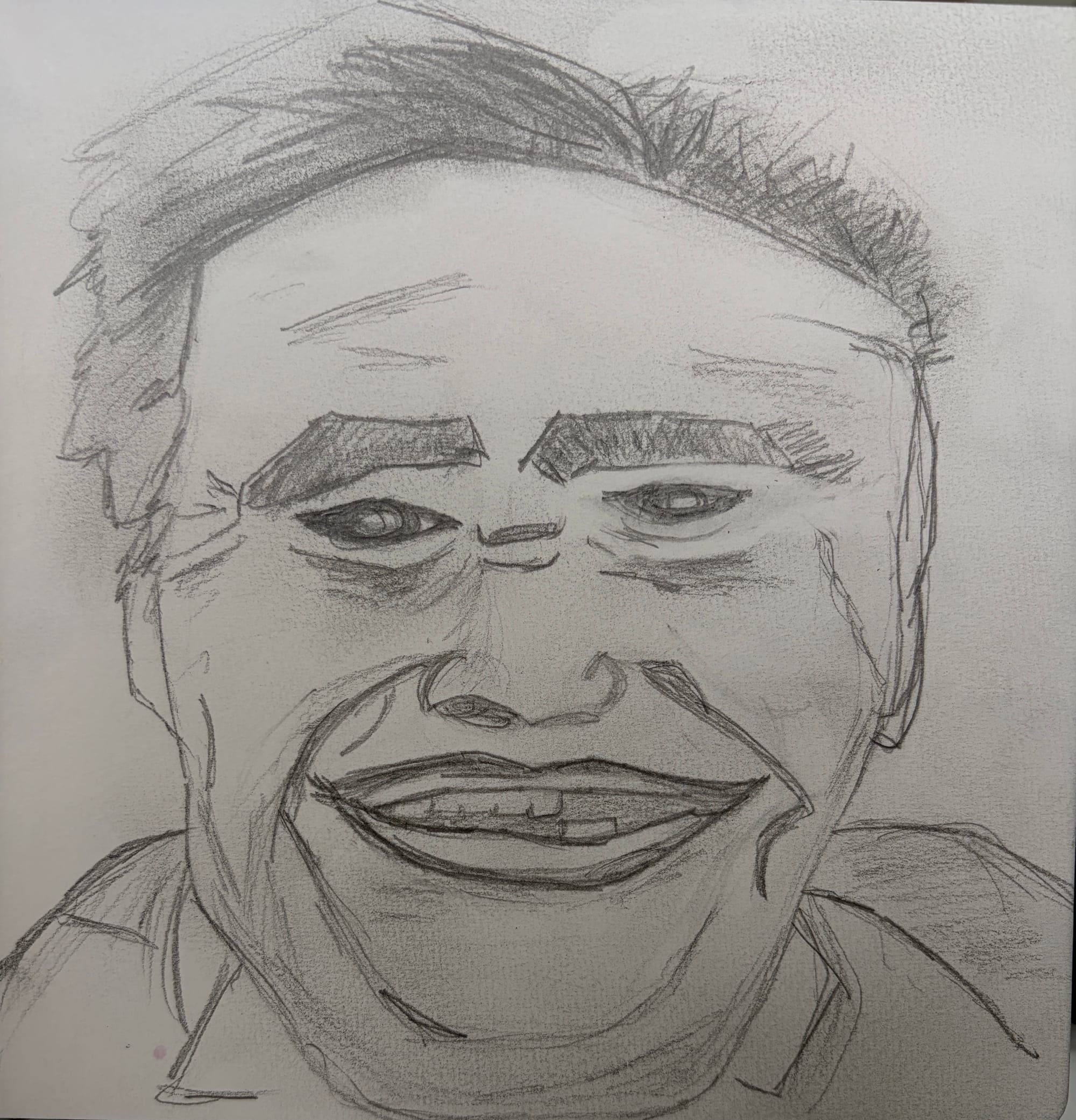

Excerpts from Hone's poem Kākā point - I was stoked because I had already drawn the power-pole. Centre; Ati Teepa, surely. Right, Hone at what looks to me like an Olympia, or maybe a Lettera? And other artworks from previous ringatoi.

So, there is

a

w

e

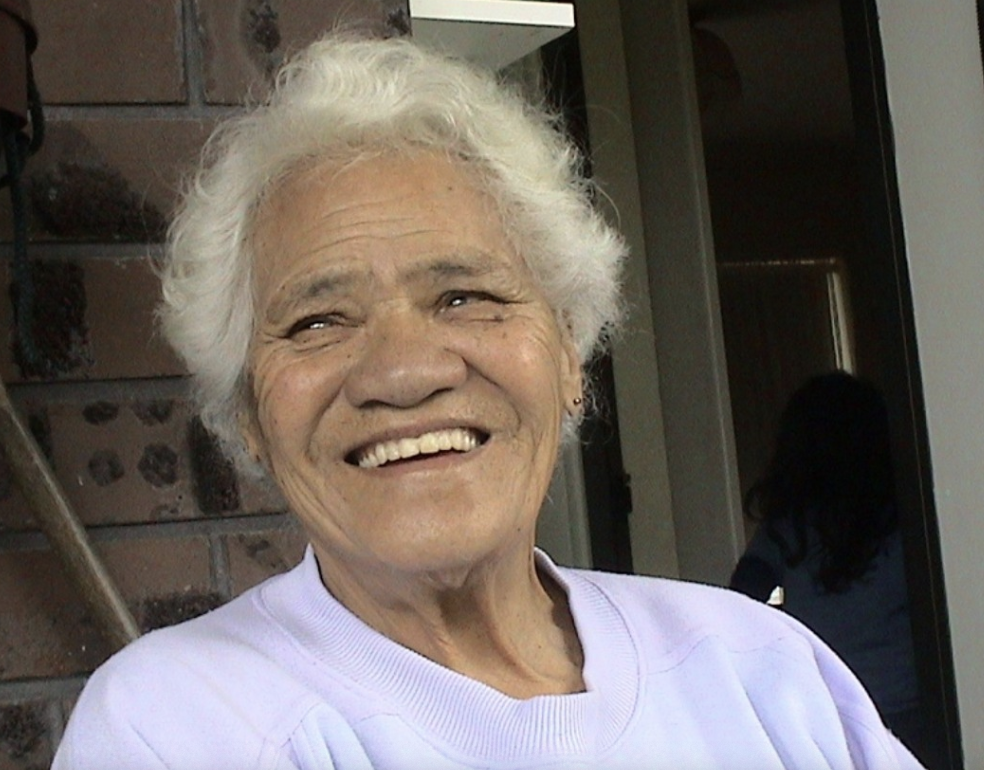

But also, I wanted to meet Hone properly. To know the story of how he came to be here, settled so far from our homeland in the the north, overlooking this great southern ocean that stretches all the way to Chile and that other raunchy lover-poet, Pablo Neruda. I say 'our homeland' because my Nan was a Tahere from Te Iringa, Ngāti Tautahi, the same hapū and whenua as Hone. I didn't even know this until I got here, but knowing it now, this trace of shared lineage, maybe I see (or want to) a bit of resemblance?. Are twinkling eyes a thing of the north, ya'reckon?

My very embarrasingly-bad sketch of Pāpā Hone on the left, in which I didn't capture the twinkle, and right, my Nan, Kaa Hura (nee Tahere) from Maramanui.

The funny thing is, I keep thinking he's coming back. It really does feel like he's here, but just away. I keep cleaning up after myself fastidiously, expecting him to come back with his bucket of kinas any minute and say, 'oi, who's that?'

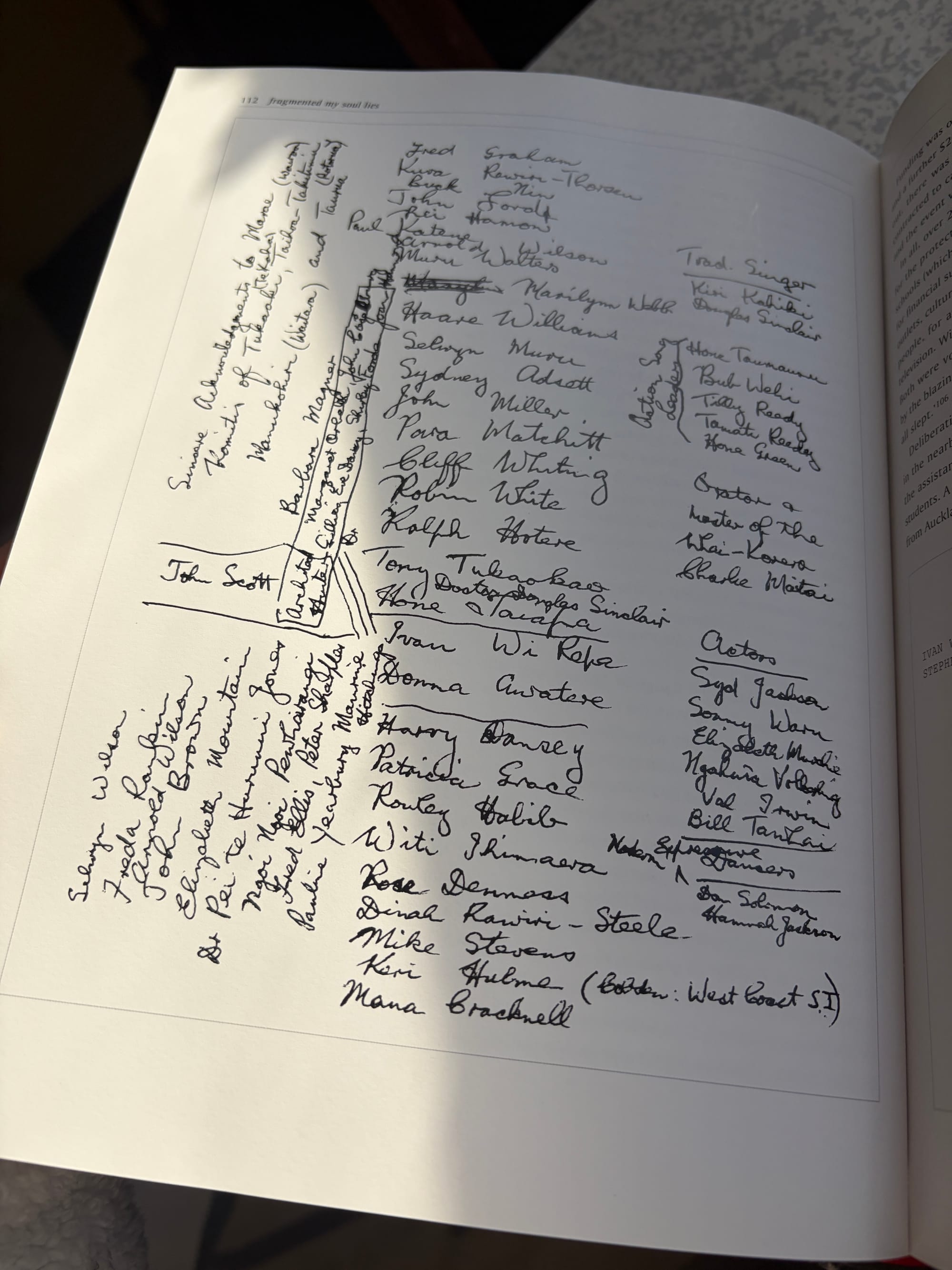

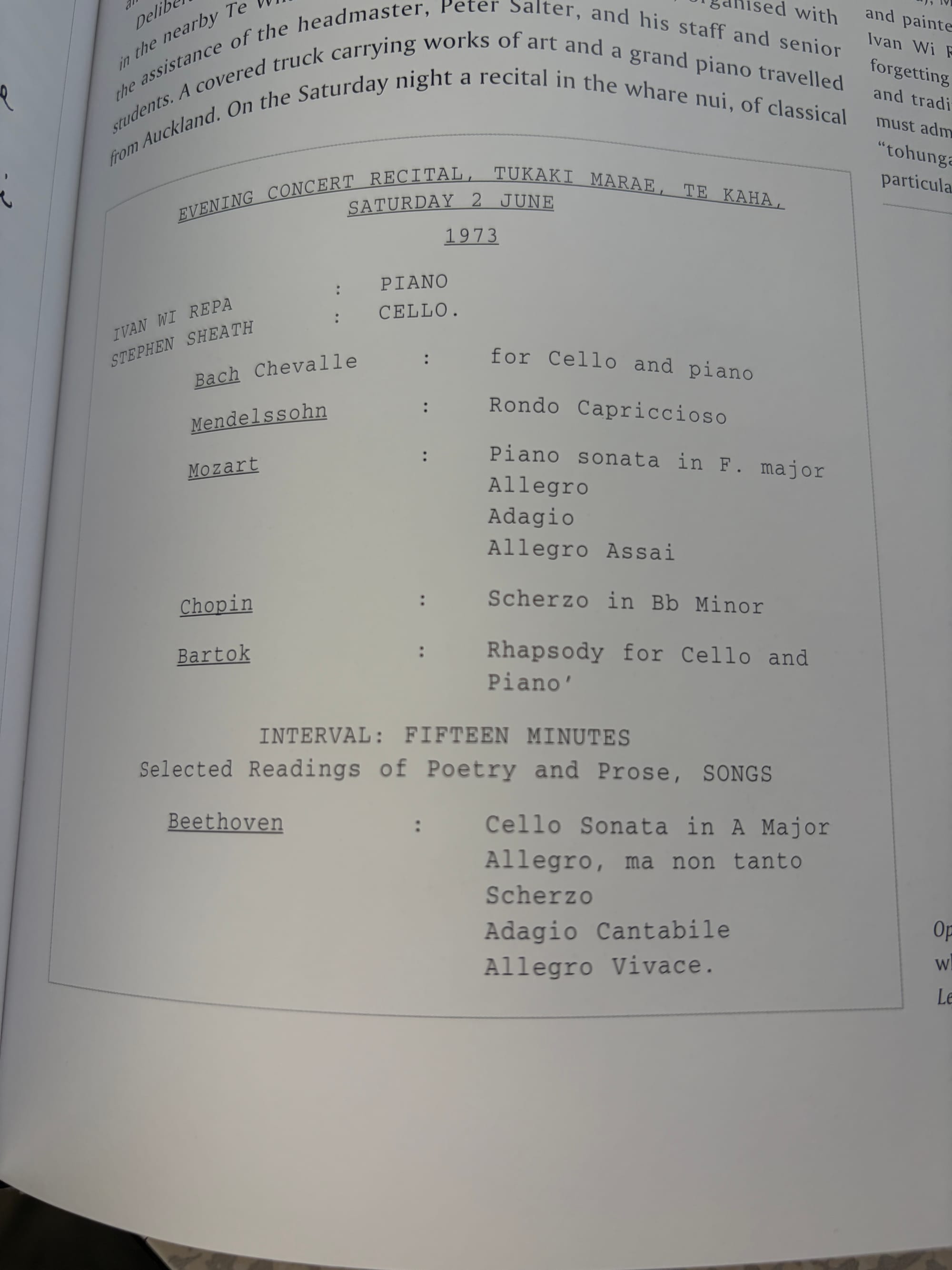

The next obvious thing to mention is the cultural legacy. Hone was an integral driving force behind the 1973 NZ Māori Artists and Writers' hui at Te Kaha, along with Haare Williams and Witi Ihimaera and Patricia Grace and Ngāhuia Te Awekōtuku and-and-and. A roll-call of greats. I've heard so much about this hui over the years, and read about it in the Koru magazines, as well the hui that followed in Wairoa and Waitara and the many hui held at Tapu Te Ranga, the mauri of which still beats through our Te Hā hui today. The idea for a Māori writers' hui was first proposed in the 50s, but it wasn't til the 70s that there were enough of us to make it viable. But even then we needed to join in with the visual artists. I remember whaea Pat telling me that the writers sometimes felt like the poor cousins, experimenting on the page with a new art form while gleaning as much inspiration and skill as they could from traditional artists.

From the pages of the Biography by Janet Hunt (p.112-113), the programme at Te Kaha, along with handwritten names of all the artists and writers Hone proposed inviting.

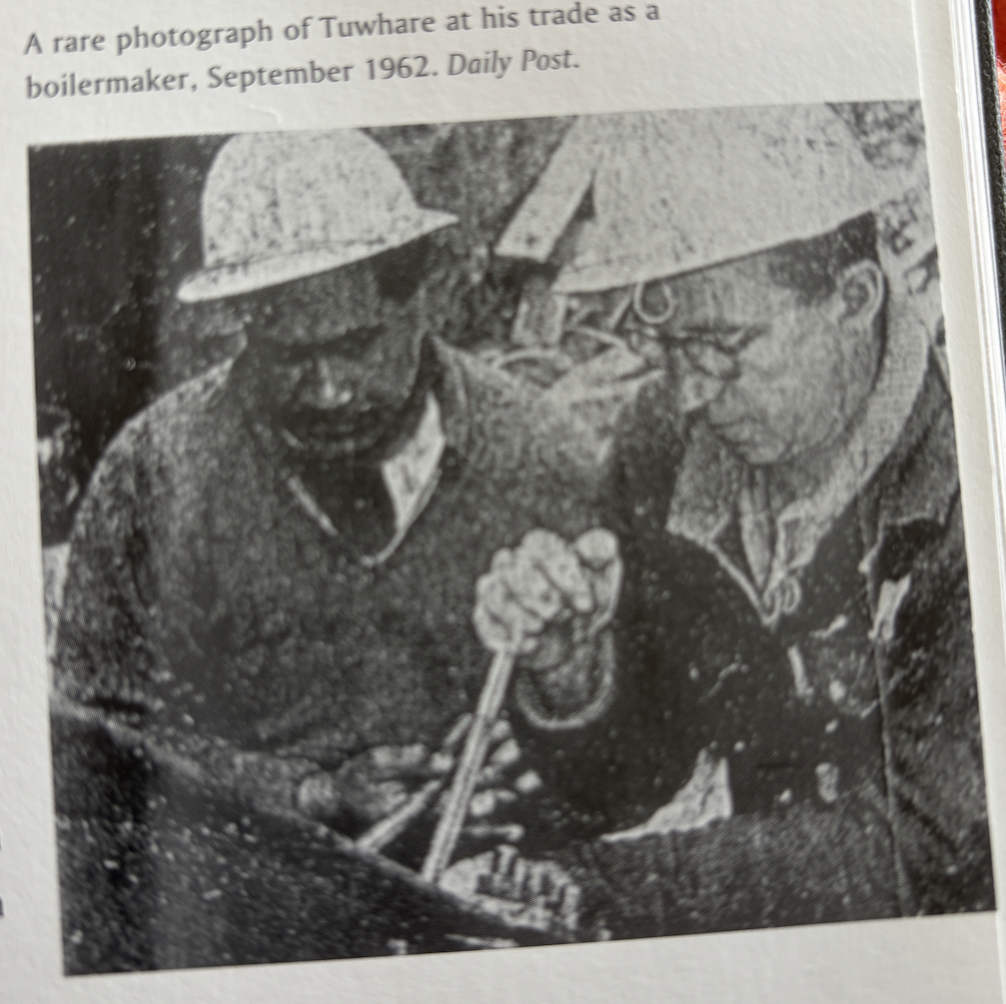

But even more than the sense of gratitude for this whakapapa, it was the details I didn't know that stood out: like that the boilermaker apprenticeship took years to gain, is an extremely highly-skilled technical trade, and was relied upon as Hone's primary income for most of his working life (duh). He was born in 1922, served in the army and spent time in Hiroshima, giving us the political poems (including No Ordinary Sun) he's most famous for. What I hadn't clocked is that Hone was raised mostly by his Dad, his Mum having passed when he was 8 and none of his four siblings surviving early childhood (so tragic - he didn't find this out until he was older).

Yet he and his Dad were thick as thieves, it seems, enduring poverty and homelessness and only sporadic schooling while working in market gardens in Auckland throughout the 30s and 40s. Hone's eldest son Rewi would also later live with him in Dunedin, as an adult, affirming paternal responsibility and affection as normal and natural for Māori as maternal affection.

From Janet Hunt's biography, black and white pictures of Hone (left) on the tools, and right with a young and dapper Tame Iti, in China.

I kept being buzzed out by all the familiar names, but in totally different contexts - Ralph Hotere (of course - who's biography is next in my to-read pile), Tame Iti (his memoir also to-read), Alistair Campbell, RAK Mason (who was also friends with, and inspiration to, Barry Brickell - his sculptures in the Michael King Writers' Centre garden feature RAK Mason's poetry). But most surprising of all, Lauris Edmond. I first discovered Lauris Edmond in an essay by Fiona Kidman in a book about New Zealand women writers and their friendships (It Looks Better on You (out of print but you can find a copy here). That book led me to The Wellington Letter, a series of laments to Lauris' lost daughter Rachel. It is a grief that Fiona describes from a distance, as a friend and witness, fellow archivist of life. The Wellington Letter gave me one of my favourite lines of poetry of all time: grief is an explosion in the mine of love. Through that book I felt like I came to 'know' Rachel - the same way people sometimes tell me they feel like they have met Darren through my writing.

And lo-and-behold, here in one of Hone's collections is a poem titled "Rachel" for Lauris. They became friends through Rachel and Rewi, who shared the same diagnosis and were being treated at the same time and place. Hone and Lauris wrote each other letters, supported one another, as writers do. The writers' world in this country has always been small. I love it.

Another geeky writer thing, maybe my favourite: No Ordinary Sun was published by a small independent press, Blackwood, in 1964. It sold 700 copies in 10 days - an unheard of number for any book of New Zealand poetry, enviable even by today's standards. A reprint of 2,000 was ordered and snapped up in similar fashion. Reprints continued the same way for decades, but for all of that, finding a copy floating around today is rare. In the very unlikely event you do stumble across a copy in a second hand shop you'll be reaching deep into your pockets to bring it home.

But the most wild thing? Hone had asked for that book to be printed by his mate, Bob Lowry, on his hand press. It took months and months to typeset, each letter and word set laboriously into the galley. Then, with half the book typeset, Bob ran out of the lower case 'e'. Tf?!! He had no choice but to print the first 700 copies of half of the book, then start again on the second - but before he could finish it, he died. Imagine it. The tragedy, the dilemma. The sheer effort and determination publishing required in those days. What are we even moaning about?

But the publishers pushed on, and the world was duly altered.

It was the Burns Fellowship, which Hone held twice (the first in '69, the second in '74), that brought him to Dunedin where he would eventually settle and be claimed in turn. He was awarded an Honorary Doctorate from both Otago & Auckland Universities (not bad for someone who never went to high school) and was a research fellow at the Hocken Library for many years. Time and space to write, as it is for every poet, was hard-won. He often had to rely on his trade to pay for the basics because poetry couldn't cover it (still won't). It was only thanks to a few writing prizes that he was able to seize this precious slip of land and retreat from his rock-star status in the city. He lived here in the Front Castle where I sit right now, from 1992 until 2008, when he passed away at the age 85. His whānau came to get him, and the connection between the peoples in the south and the peoples in the north continue to this day. Whakapapa at its best.

The next 16 years have been spent in restoration and fundraising (his whānau talk about this journey in detail in the Homesteads doco). The dream: that the crib can continue to provide inspiration and time and space and material support to Māori poets and lovers and dreamers. Unlike the many residencies in the names and former homes of Pākehā writers, this is the first and only one in the home of a Māori writer. Knowing this, the gift of it, the need of it, the sacrifice for it, then and still, only makes me feel... more jittery!! Lol.

But luckily, with that trademark twinkle of his Dad's, Rob says at the end of the doco "it's also just a place to come and relax."

Which is lucky, cos it's about the only thing I feel like I'm excelling at right now!

Before I go, I want to close by sharing a poem by Jean McCormack, who, like many a literary wife, could wield a pen pretty well herself. Jean passed away in 2020, aged 95, and this poem was re-published as part of a tribute to her in Newsroom.

It's got an ache to it that I'm a sucker for.

Sand

I walked on this beach

with the Māori father of my sons

fifty years ago and more…

He didn’t tell me the grains of sand

on the beach were his.

We crossed the creek

and wrote our names on a rock

encircled with a heart.

We danced at the Pirate Shippe

waltzes and foxtrots

and the Levita.

We move in different times and spaces now.

I walk the same beach in the winter.

And still no word from him about the sand.

Thank you so much to the Hone Tuwhare Trust. He mihi mutunga kore ki a koutou me tēnei honore NUI! Anō hoki ki a Isla Huia and Ashleigh Zimmerman (who also hold the residency this year). Ati Teepa, Tracey Tawhiao and Tame Iti were the inaugural recipients.

Pps: Southern whānau, I am thinking of doing a zine / journaling workshop here at Kākā point next weekend, Saturday 21st... are ya's keen?